May 17, 2017 | gentrification

Gentrification is just over 50 years old. It may have been happening in Roman Times when a couple of huts were knocked down to make way for the emperor’s swimming pool, but the term itself did not come about until 1964 when a British social scientist used the term “gentrification” when discussing changes observed in London’s inner neighbourhoods.

As far as Toronto was concerned, when the middle class wished to buy a house 50 years ago, they usually bought new. For many years that often meant the suburbs. The suburbs were easily connected to the city and a simple drive away before traffic became a nightmare. Older neighbourhoods back then would be left behind by the middle class and subsequently declined in value. Sometimes the properties would fall into disrepair. Many local businesses would close down or just make due with less profit. The poor, the underclass, the new immigrants, the outcast, the rebels, the artists and those who just love to live in the city were left behind. Often theses called declining Toronto neighbourhoods would have more rentals, and less maintained properties.

I would say it was not really until the 1970s when the idea of transforming an existing Toronto neighbourhood into something where the middle class would return came about. Yorkville started off as a hippie hangout, but soon became a posh centre-piece to downtown Toronto.

Since then, most neighbourhoods within a certain radius from downtown Toronto have undergone some kind of gentrification. In the 80s and 90s, it occurred in Cabbagetown, Little Italy and High Park. By the 2000s, we have seen how neighbourhoods have transformed in Toronto from the Junction to Leslieville, Corktown to Parkdale. The list of reasons for gentrification are long: Less commuting time to work, the suburbs are isolating and soul-less, the desire for walkable communities, and better work/love/play opportunities in the city – to name a few.

Regardless of the reasons, people are returning to cities in huge numbers all over the world. Highly diversified mega-cities are becoming a greater magnet, attracting people and capital to their multi-faceted economy with a strong connection to the growing information economy. With this success, city nieghbourhoods can really change.

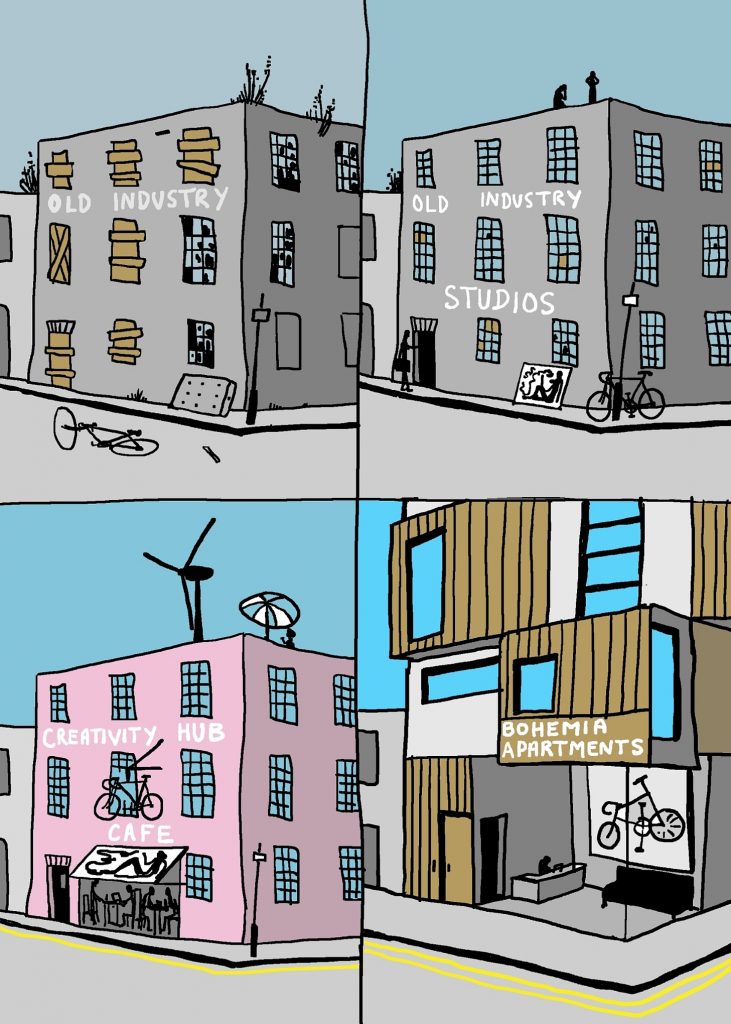

Take the neighbourhood of Brixton in south London. In 1981 it was the scene of riots at time when this neighbourhood had high unemployment, high crime, poor housing and no amenities. It was, and still is, populated largely by an Afro-Caribbean community. As in many emerging neighbhourhoods, Brixton first attracted artists from central London looking for less expensive accommodations and a place to make art. A bohemian art scene popped up followed by middle class individuals seeking less expensive homes. In no time there were galleries, pop-up shops, bars, cafes, delicatessens and design stores.

It all sounds very glam, but there is some debate as to whether this process is beneficial to everyone.

One could argue that some people have been displaced because of this gentrification. They are forced out of their homes by rising rents and prices, and the city, whether it is London or Toronto, does not make the necessary changes to create affordable housing.

Others will argue that this gentrification prevents a neighbourhood from declining further, bringing an infusion of funds to improve buildings, create jobs through new businesses, and allow a place for people priced out of more expensive neighbourhoods to buy a home.

Gentrificiation is not a given right for a modern city. Without a strong, diversified economies, gentrification bypasses some cities. Cities that have relied heavily on one industry can be very vulnerable. Just look at Detroit who relied on the automotive sector. With many of those high paying middle class blue collar jobs going overseas, Detroit’s only game in town has lead to a plummeting employment rate and a city less than half its peak population. Even though we are seeing glimmers of hope in Detroit and Buffalo more recently, they have declining for years, and may never recover.

Cities are also shrinking is population and in wealth in Canada. Saint John, New Brunswick is down 3% in size since 2006. It seems to be the smaller towns that are really suffering, largely because the jobs are just not there. From Kapuskasing, Ontario down 36% from its peak population to Wabana, Newfoundland down 70.8% since its peak. Smaller cities and towns have certainly had a harder time.

What is interesting now is how some cities have become so overwhelmingly in-demand that it has sparked the growth of nearby smaller cities that were once on the decline, but have since turned around. When San Francisco became crushingly expensive in a way that Toronto hs never known, many turned to the far less expansive Oakland just across the Bay. As Oakland became more expensive, many went further out of Oakland to look for property.

A similar thing has occurred here in Toronto. As Toronto becomes more expensive, many have turned to Hamilton. And we have to give the City of Hamilton some credit. They have worked very hard to diversify an economy that was mostly based on steel. Hamilton may have been a rust-belt city, but it benefited from its proxity to Toronto.

In a sense, the gentrification that has been happening in Toronto has tipped over into other municipalities. Whatever you may think of gentrification in Toronto or Hamilton or anywhere, whether it a is force for improvement or a destroyer of affordable housing, one thing is understood…

Once it reaches a tipping point, gentrification cannot be contained or fully controlled. Once it is rolling, it is often like a runaway freight train. It may take awhile to take hold, but once it does, there’s almost no chance of turning back.